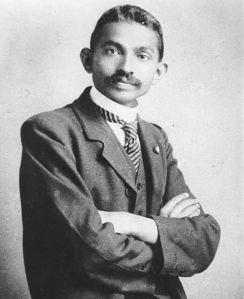

During the Zulu rebellion of 1906, while Sgt-Major Mohandas Gandhi was leading the Indian Stretcher-bearer Corps, he wrote a series of dispatches describing their actions. These reports were printed in Indian Opinion, the newspaper where he had previously advocated that Indian volunteers should be allowed to take up arms in order to defend the country that they lived in.

Gandhi waxed poetically about the character benefits to life as a soldier. The man who volunteered would learn to appreciate simple food, keep regular hours, and develop camaraderie with men in a small space. Biographer Joseph Lelyveld observes that Gandhi seemed to feel that the battlefield, if nothing else, offered discipline.

His reports put the best face on their efforts during their six weeks of service. A modern reading, however, suggests that much of what they did was simple make-work. The Zulus, armed with spears, were no serious threat to the British, and Gandhi does not attribute a single injury to the natives. Instead, they physically carried men such as Private Sutton, “whose toe was crushed under a wagon wheel.”

On the evening of July 2, Gandhi’s Corps received orders to prepare to march in a combined column early the next morning. They packed up two days rations, their blankets and stretchers, and at 3am headed out. In theory, the cavalry at the end of the column would protect the 20 unarmed men as they traveled through Zulu territory. But instead, the horsemen galloped ahead.

The stretcher-bearers tried to keep up, but it was “a hopeless task.” The gap widened as the miles passed, and once it became light enough to see, the cavalry traveled even faster. Gandhi and his men were left behind. There was nothing they could do except pursue their escort.

It was then that they met an armed native “who did not wear the loyal badge.” The man disappeared into the terrain, perhaps after calculating the 20-1 odds, but Gandhi wrote, “Probably we had a narrow escape.”

The stretcher-bearers struggled along all day, crossing and recrossing the shallow Umvoti river, and were so worn out that the troopers mocked them when they stopped for the evening. What would they do if they actually had to carry any wounded? Gandhi stiffly replied that God would have provided strength.

After being abandoned by his “band of brothers,” did Gandhi really feel like he was contributing to the war effort, and earning the respect of the white minority engaged in repressing him and his people? His efforts to put aside the differences of the two communities and forge a common bond were certainly well intentioned, but this incident must have deeply irritated him. He described the events of July 3 as “a day that will ever remain memorial to the members of the Corps.”

Have you ever made an offer to help, only to have it insultingly rejected?