On January 30, 1948, Mohandas K. Gandhi made his final sacrifice. After his assassination, there was talk of embalming him so that a last tour could be made, allowing the mourning millions one last opportunity to receive the darshan of the Mahatma—the great soul. His long-time secretary, Pyarelal, insisted that Gandhi absolutely would not approve, and had desired prompt cremation. Less than twenty-four hours after three bullets ended his life, Gandhi’s funeral pyre was set ablaze.

Like Jesus, commentators observed, Gandhi was killed on a Friday. In the immediate hours after his death, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru spoke on All India Radio. “The light has gone out of our lives,” he told the nation. The funeral would take place on Saturday, and he invited the people of Delhi to gather along the route. For those who lived elsewhere, Nehru asked them to take part “in this last homage” by observing “a day of fasting and prayer.”

The funeral procession was four miles long, stretching from Birla House, where he’d been killed, to the funeral pyre prepared of sandalwood on the banks of the sacred Yamuna River. Since Gandhi was estranged from his oldest son, and the second was carrying on the work in South Africa, the privilege of lighting the pyre went to the third son, Ramdas, who flew in from the Central Provinces. When he arrived, the procession began.

An estimated 1.5 million people gathered along the route. The photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White, who had interviewed Gandhi hours before he was shot, braved the crowds to document the occasion. In her book, Halfway to Freedom, she concluded “Gandhiji’s assassination was the tragic climax to a long history of carefully nurtured religious antagonisms.” But those antagonisms softened in light of the senseless killing: M.A. Jinnah, and other Muslim politicians, offered public condolences.

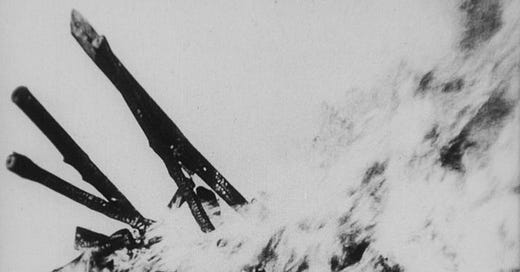

The procession proceeded at about 1 mile per hour, frequently blocked by crowds bursting onto the road. At 4:20, they arrived at the pyre, and his body was carefully placed on the platform which had been built for the occasion. With his younger brother by his side, Ramdas ignited the pyre—doused with ghee—at 4:45.

The fire burned into the early hours of the morning, and Gandhi’s ashes were collected and viewed around the country, then mixed into the rivers which gave India life.

In Nehru’s radio address, he said:

The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light. The light that has illumined this country for these many years will illumine this country for many more years, and a thousand years later, that light will be seen in this country and the world will see it and it will give solace to innumerable hearts.

Truth.

What funeral has impacted your life the greatest?