I’ve written before about how Gandhi organized volunteers for the British army in the 20th century during World War One and the Zulu Rebellion. At the end of the 19th century, he did the same thing during the Boer War in South Africa. This seems like a good point to give a brief overview of the geopolitical situation.

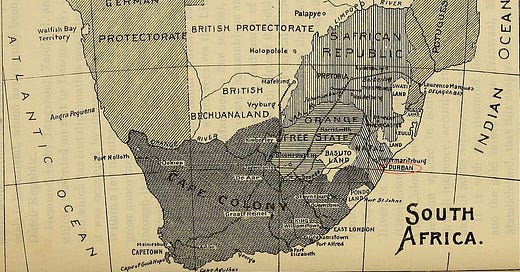

What eventually became the Union of South Africa was at the time four distinct political subdivsions. Natal and the Cape Colony covered the southern coast, and were controlled by the British. They had once been populated by Dutch farmers (Boer means ‘farmer’ in Dutch), but rather than live under British adminstration, they retreated northward and inland. There, the Boers displaced the native Africans and formed the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. The situation might have remained stable—the Boers “were a farming people, devout and dogmatic”1 who wanted to be left alone—but in 1886, they did something that attracted international attention.

They discovered one of the richest veins of gold on the planet.

The resulting economic expansion drew many to the Transvaal, including Indian merchants, which created the legal dispute that had summoned Gandhi in 1893. By 1898, more than 25% of the global gold supply was produced there, and the British eyed the wealth with envy. In 1899, they began massing thousands of troops on the border.

Paul Kruger, president of the Transvaal, demanded they be withdrawn. When the ultimatum expired, the Boers struck first and invaded Natal on October 12.

Like all of us, Gandhi’s thoughts and opinions evolved over the course of his life. While he’s fiercely associated with opposition to the British, he wasn’t born that way. During his formative years in South Africa, he was proud to be a subject of the British Empire.

This is clear in the letter he sent on October 19, a week after fighting began, explaining there were many in the Indian community willing to volunteer and serve without pay.

The motive underlying this humble offer is to endeavour to prove that, in common with other subjects of the Queen-Empress in South Africa, the Indians, too, are ready to do duty for their Sovereign on the battlefield. The offer is meant to be an earnest of the Indian loyalty.

Gandhi’s name was the first on the list of thirty volunteers; he explained the number might seem small, but it represented a quarter of the local Indian men who understood English. He was told their services were not currently needed, but “should the occasion arise; the Government will be glad to avail itself” of the help.

That day arrived in December, and Gandhi would soon find himself on the battlefield. But that’s another story.

Can you think of a time you were motivated by greed?

Gandhi Before India (Guha, 2013) p. 67